Lincoln's Notes

Understanding Dynamic Programming with Recursion Call Trees

What is Dynamic Programming?

Dynamic Programming is a fascinating set of algorithm design techniques.

It involves breaking down a problem

into sub problems and then combining the sub solutions to compose the solution

to the original problem.

Each of the sub problems is further divided into sub-sub-problems.

This repeating nature of dynamic programming naturally lends itself to coding with recursion.

Dynamic Programming can be confusing to some people. That is because we very rarely use it

in out day to day jobs. As Programmers, we mostly do Imperative Programming,

i.e. we specify a set instructions to achieve a objective. More often than not this involves managing

records in some kind of a data store(RDBMS, File System, NoSQL etc).

Dynamic Programming can help us get a better understanding of Combinatorial Programming.

Combinatorial Programming

A certain set of problems involves choosing an optimal solution from an enormous set of possible solutions. The straight-forward approach to these problems would be to enumerate all the possible permutations/combinations. Then evaluate each of these permutations/combinations to filter the appropriate ones.

Consider the 4-Queen's problem. We can generate all possible solutions with nested for loops:

for queen_1_position_in_row_1 in range(4);

for queen_2_position_in_row_2 in range(4);

for queen_3_position_in_row_3 in range(4);

for queen_4_position_in_row_4 in range(4);

is_valid(queen_1_position_in_row_1, queen_2_position_in_row_2, queen_3_position_in_row_3, queen_4_position_in_row_4)Most solutions to Dynamic Programming problems generate and evaluate numerous probable solutions.

Although the above snippet is easiest to comprehend, it is not the most efficient.

We can use Recursion to code more elegant and efficient solutions that do not involve nested for-loops.

We will see how "Recursion" can be used to emulate the nested for-loops that we used in the above snippet.

Top Down and Bottom Up

Solving DP problems with recursion is a top-down approach. Although DP problems also have bottom-up solutions, they are not as intuitive as the top-down solutions.

Our goal in this post is to use recursion call trees to demystify the code and uncover common patterns in these types of problems.

In the process, we will also get a better understanding of the time complexity for some of the solutions.

I have picked some problems from "Cracking The Coding Interview" by Gayle Laakmann Mcdowell

- Triple Steps

- Changing $100

- Permutations

- N Queens

- Power Set

- Robot

1. Triple Steps

Implement a method to count how many possible ways the child can run up the stairs.

To develop the solution, we will work with a 5 step staircase.

This is a combinatorial problem. One strategy would be to enlist all possible combinations and

then filter out the invalid ones.

for first_jump in (1, 2, 3):

for second_jump in (1, 2, 3):

for third_jump in (1, 2, 3):

for fourth_jump in (1,2, 3):

for fifth_jump in (1,2, 3):

...

...

will_this_sequence_of_jumps_lead_to_the_top(...)If we have a 5 step staircase, then we need at least 5 nested loops so that [jump 1 step, jump 1 step, jump 1 step, jump 1 step, jump 2 step] is

generated as a probable solution.

This solution will not be able to handle a 6 step staircase. We will have to recode for a 6 step staircase with 6 nested for-loops.

Also some of the for loops could have been optimised. For e.g. if the first_jump is 3, then the second_jump cannot be any number greater than 5-3.

Let us see how recursion allows us to generate(or simulate) dynamic number of nested for loops.

The Recursive Solution

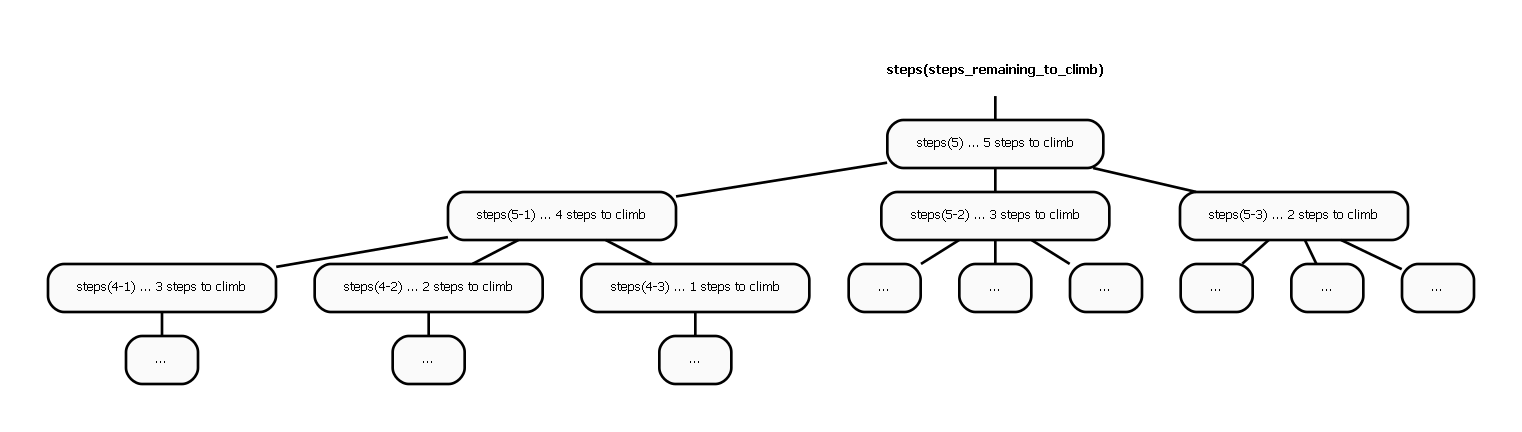

We are required to climb 5 steps(ref. the tree below). We start by :

- jumping 1 step ... we will land on a node with 4 steps remaining

- or jumping 2 steps .. we will land on a node with 3 steps remaining

- or jumping 3 steps .. we will land on a node with 2 steps remaining

Then, we repeat the same set of choices for every node.

As the process is repeated, we will end up with "negative", or "0" nodes.

Reaching a "0" node means we have reached the top of the staircase(There are no more steps to cover). All the paths from the root to "0" node represent a valid path to take to reach the top of the staircase.

Let's evaluate how we could end up with a "negative" node. Say, for example, we start by jumping 3 steps, and then jump another 3 steps. The remaining steps will be 5-3-3=-1 If the "remaining" value of a leaf is negative, then that path is not a valid solution.

The Hidden for-loops

We had multiple nested for-loops in the original simplistic solution. They seem to have disappeared from the recursion based solution!

On closer observation, we can see that there are 3 recursive invocations in the method. That is a HIDDEN for-loop with i=0 to i=3.

And what about nesting? The original simplistic solution had 5 levels of nested for-loops.

In the recursive method, the level of nesting is controlled by the recursive code. The body of the method usually has an decision to make:

- Either make another set of recursive calls thus emulating a DEEPER NESTED for-loop

- Or return without invoking itself

Collecting All the Solutions

The problem statement asks to count the number of ways/paths that exists. However, we will try to list out the actual paths.

How can we write code to collect all the valid paths? We will look at 3 code snippets:

Solution 1 Try it on repl.it

def steps_1(remaining_steps, partial_path, all_paths):

# partial path gets added to "global" var all_paths

# all_paths will contain the final result

if remaining_steps < 0:

pass

elif remaining_steps == 0: # we have reached a valid path leaf

all_paths.append(partial_path)

else:

steps_1(remaining_steps - 1, partial_path[:] + [1], all_paths)

steps_1(remaining_steps - 2, partial_path[:] + [2], all_paths)

steps_1(remaining_steps - 3, partial_path[:] + [3], all_paths)

return all_pathsHere, we pass a partial_path to the function.

If the partial path is valid (remaining_steps==0), then it gets added to the list containing all valid paths.

Let us compare this code to the the call tree. The python function is a programmatic representation of the call tree. We can see how this code ends up building the call tree that we just saw.

There are a few observations:

- Python solution is succinct. Note how we use the

[:]operator to duplicate the array. - We are creating

partial_patharrays some of which are eventually discarded(not added toall_paths) because they do not form a valid solution. - We are using global variables in the form on

IN/OUTparameters to the function. Of course, we can hide these parameters from the end user by using a wrapper function. But, if possible, we would like to eliminate these "globals" altogether.

Let us take a look at another solution:

Solution 2 Try it on repl.it

def steps_2(remaining_steps, partial_path):

# still using partial paths, but no all_paths

all_paths = []

if remaining_steps < 0:

pass

elif remaining_steps == 0:

all_paths.append(partial_path) # we have reached a valid path leaf

else:

# join all the partial paths coming in from the child invocation

all_paths.extend(steps_2(remaining_steps - 1, partial_path[:] + [1]))

all_paths.extend(steps_2(remaining_steps - 2, partial_path[:] + [2]))

all_paths.extend(steps_2(remaining_steps - 3, partial_path[:] + [3]))

return all_paths- We eliminated one global(

all_paths) - The return type is array of arrays

[[]] - On reaching a successful leaf (

remaining == 0), we return[partial_path].partial_pathitself is an[]

The function looks much cleaner. We do not have to pass the extra in/out parameter all_paths.

We are still creating partial_path for all prospective solutions.

Instead, we could construct a path only if we are certain that it ends on on 0 node.

To achieve this, we have to take action on the way back, while the recursion stack is being unwound.

Solution 3 wil show how this can be done.

Solution 3 Try it on repl.it

#!/usr/bin/env python3

def steps_3(remaining):

all_paths = []

if not remaining:

all_paths.extend([[]]) # we have reached a valid path leaf

elif remaining < 0:

pass

else:

one_paths = steps_3(remaining - 1)

five_paths = steps_3(remaining - 2)

ten_paths = steps_3(remaining - 3)

all_paths.extend(list(map(lambda x: x[:] + [1], one_paths))) # can use list comprehension

all_paths.extend(list(map(lambda x: x[:] + [2], five_paths)))

all_paths.extend(list(map(lambda x: x[:] + [3], ten_paths)))

return all_pathsHere, we are not creating partial_path for every prospective solution.

Instead, we add a

nodeto the path on thereturnwhen the stack is being unwound. This substantially reduced the memory footprint of the code snippet.

The sub-problems return a non empty array of valid paths.We then extend the non empty array with the current node.

If we look at the call tree, we will notice that certain nodes have the same "remaining" value.

Memoization

We could cache the result from the first exploration of f(a) and use it whenever f has to be invoked again.

This technique is called memoization and will have improve efficiency of our implementation.

2. Change

Given an infinite number of $2, $3, and $5, write code to calculate the number

of ways of representing $n dollars.

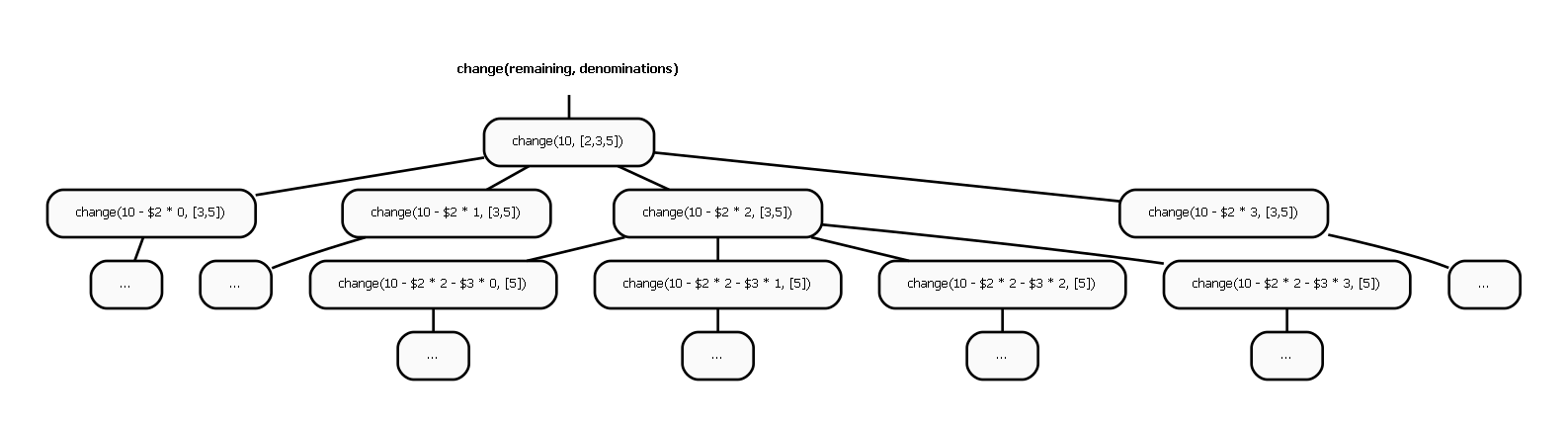

As in the last problem, we have choices to make at each node:

Starting from the top node, there are multiple paths that can be taken:

- Use 0 of $2 and then find change for 10-2*0 using

[$3, $5] - Use 1 of $2 and then find change for 10-2*1 using

[$3, $5] - Use 2 of $2 and then find change for 10-2*2 using

[$3, $5] - Use 3 of $2 ....

- ...

- Use 0 of $3 and then find change for 10-3*0 using

[$5] - Use 1 of $3 and then find change for 10-3*1 using

[$5] - Use 2 of $3 and then find change for 10-3*2 using

[$5] - Use 3 of $3 and then find change for 10-3*3 using

[$5] - ...

- Use 0 of $5 and then find change for 10-5*0 using

[] - Use 1 of $5 and then find change for 10-5*1 using

[] - Use 2 of $5 and then find change for 10-5*2 using

[] - Use 3 of $5 and then find change for 10-5*3 using

[] - ...

Solution Try it on repl.it

#!/usr/bin/env python3

def change(amount, options):

if not amount: # zero amount left. We have a valid solution path

return [[]]

elif amount < 0:

return []

else:

solutions = []

for i, option in enumerate(options): # consider every option

option = options[i]

rest = options[i+1:]

for option_amount in range(option, amount + 1, option): # generate option x 0, option x 1, option x 2 ....

remaining_amount = amount - option_amount

change_for_remaining = change(remaining_amount, rest)

this_plus = [x[:] + ["${}x{}".format(option, int(option_amount/option))] for x in change_for_remaining]

solutions.extend(this_plus)

return solutionsThe structure of this solution is similar to the earlier steps solution.

A new for loop has been introduced because the number of choices is much larger

than the steps solution(as seen in the tree).

The solutions from the sub problems are still collected into the solutions array.

And we create the solution path while unwinding(returning) from a successful leaf node.

3. Permutations

Write a method to compute all permutations of a string of unique characters.

Many of the dynamic programming problems involve exploring the universe of combinations.

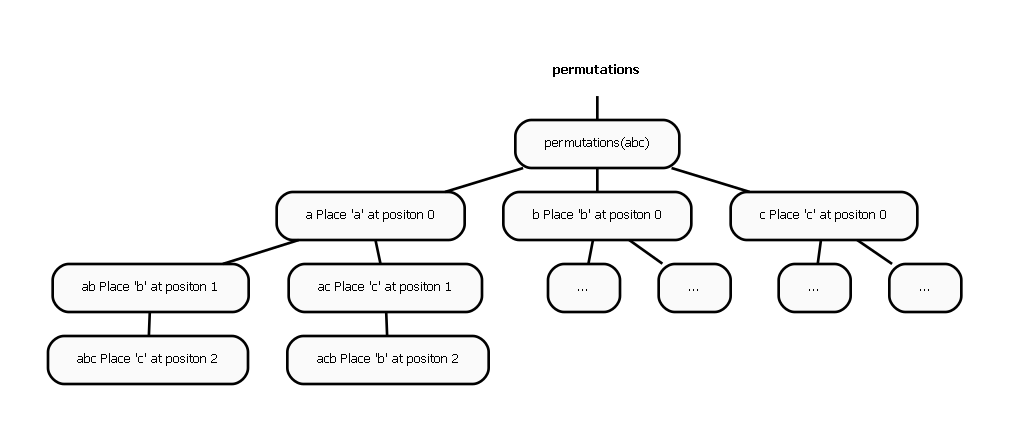

At every node, we have to make choices on which "branch/choice" to explore. For each problem, it is necessary to understand what the choices are. In this case the first choice requires us to decide what character to place at position 0

- Place "a" at position 0 and fill out rest of the positions with

[b, c] - Place "b" at position 0 and fill out rest of the positions with

[a,c] - Place "c" at position 0 and fill out rest of the positions with

[a,b]

If we place "a" at position 0, then we have [b, c] to fill positions 2 and 3.

After placing "a" at position "0", we again will have to decide what to do at position 1.

We can either place "b" or "c" at 1.

The call tree gives us a good visualization of the choices.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

def permute(choices):

if not choices:

return [[]] # we have reached a valid path leaf. In this case, every path is valid.

else:

all_results = []

for i, this in enumerate(choices):

rest = [choices[j] for j in range(len(choices)) if j != i]

permute_rest = permute(rest)

this_and_permutations = [[this] + permute_rest[k] for k in range(len(permute_rest))]

all_results.extend(this_and_permutations)

return all_results

if __name__ == "__main__":

permutations = permute("abc")

for permutation in permutations:

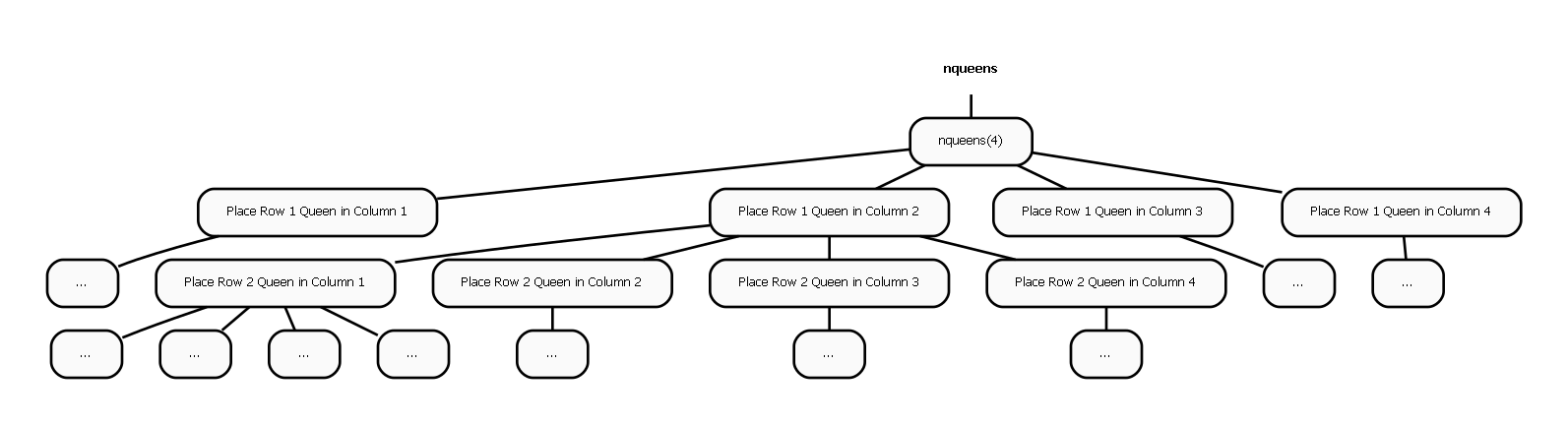

print(permutation)4. N Queens

Place N queens on an N x N chessboard such that no two queens attack each other.

Here again, we have to grapple with the combinatorial space of queen positions. Consider a 4x4 ChessBoard

__ __ __ __

row 1 |__|__|__|__|

row 2 |__|__|__|__|

row 3 |__|__|__|__|

row 4 |__|__|__|__|

A solution takes the form of an array [i, j, k, l] and implies that we can place a

queen at column i in row 0, column j in row 1 , column k at row 2, and column l in row 3

The total possible Queen combinations is nn.

A Queen has n possible positions in row 1 ( (row1, col1), (row1, col2), and so on.

Since we have N queens and N rows, we end up with nn possible positions.

We have to consider each of these positions and weed out the illegal ones.

The algorithm is similar to the one for permutations What are the choices? There are 4 possible positions for queen in row 1

- Place a Queen in row 1, column 1

- Place a Queen in row 1, column 2

- Place a Queen in row 1, column 3

- Place a Queen in row 1 ,column 4

When we select the first option, we have have another choice to make. Where to place the queen in row 2. Again we have 4 choices

At every node, we have to decide if the choice is viable.

for e.g., we decided to place first queen at

At every node, we have to decide if the choice is viable.

for e.g., we decided to place first queen at row0, col0, then at the next node we

have to choose position for queen at row2.

We can choose row2, col1. But this is not valid since we will end up with 2 queens in same column.

let us see how the pseudo code would look:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

def valid_combination(partial_solution):

raise Exception("Not Implemented")

def n_queens(n, partial_solution, all_solutions):

if len(partial_solution) == n:

all_solutions.append(partial_solution)

else:

for i in range(n):

next_partial = partial_solution[:] + [i]

if valid_combination(next_partial):

n_queens(n, next_partial, all_solutions)5. Power Set

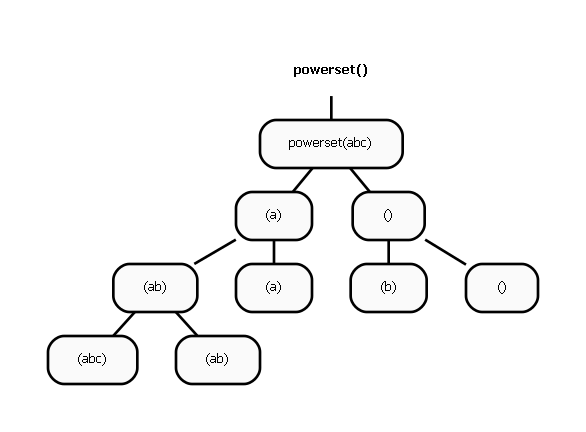

Write a method to compute the Power Set of Set A. Power Set is the set of all Subsets of a set.

The choices we have to make in the Power Set algorithm are pretty simple.

To compute the Power Set of a,b,c,d, we first compute the Power Set of b,c,d.

Then we build 2 sets from the Power Set of b,c,a

- First we create a new set by appending

ato all elements of the result - Then we create another set by Not appending

ato all elements of the result

The combination of these 2 sets gives us the Power Set of a,b,c,d

Looking at the code will make it obvious

#!/usr/bin/env python3

def power_set(set_elements):

if not set_elements:

return [[]]

else:

all_results = []

this = set_elements[:1]

rest = set_elements[1:]

power_set_for_rest = power_set(rest)

with_this = [this + x for x in power_set_for_rest]

without_this = power_set_for_rest

all_results.extend(with_this)

all_results.extend(without_this)

return all_results

if __name__ == "__main__":

for i, r in enumerate(power_set([1, 2, 3, 4]), 1):

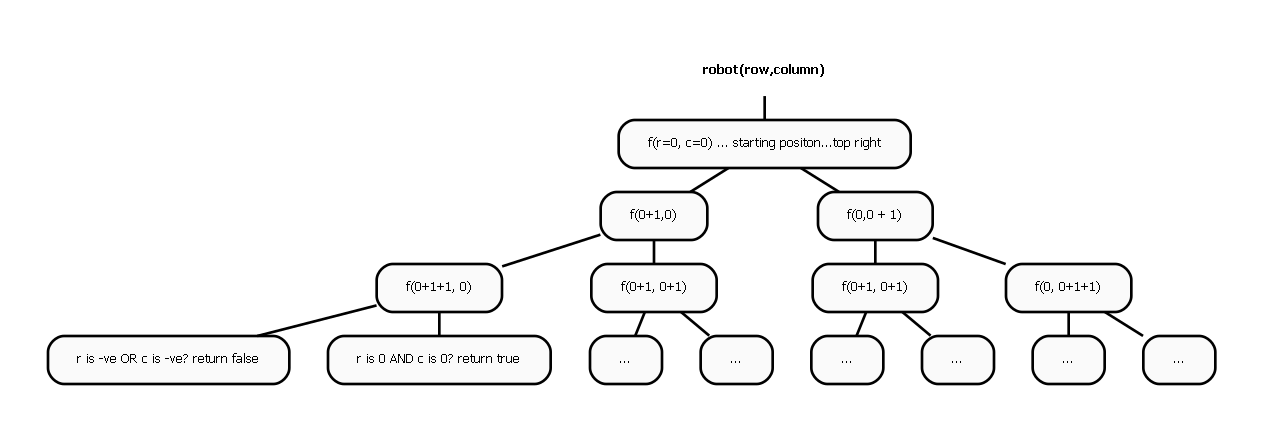

print(i, " ", r)6. Robot in Grid

Imagine a robot sitting on the upper left corner of grid with r rows

and c columns. The robot can only move in two directions, right and down, but

certain cells are "off limits" such that the robot cannot step on them.

Design an algorithm to find a path for the robot from the top left to the

bottom right.

Here again, we can visualize robot movement using a "chess board"

____________

|x_|__|__|__|

|__|__|__|__|

|__|__|__|__|

|__|__|__|__|

Let's assume the top left is (x=0,y=0) if we go down, then the new position would be (x=0, y=0+1) if we go right, then the new position would be (x=0+1, y=0)

at every node, we have 2 choices: go down, or go right

if we reach the destination, then we return an array within an array that will be filled up with nodes as the stack is unwound.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

MAX_X = 10

MAX_Y = 10

def move_robot(current, dest):

x, y = current

if current == dest:

return [[]]

elif x > MAX_X or x < 0 or y > MAX_Y or y < 0:

return []

else:

paths = []

down = x, y - 1

down_paths = move_robot(down, dest)

if down_paths:

down_paths_with_current = [["down", down] + p[:] for p in down_paths]

paths.extend(down_paths_with_current)

right = x + 1, y

right_paths = move_robot(right, dest)

if right_paths:

right_paths_with_current = [["right", right] + p[:] for p in right_paths]

paths.extend(right_paths_with_current)

return paths

if __name__ == "__main__":

all_paths = move_robot((3, 7), (6, 4))

for path in all_paths:

print(path)Conclusion

Call trees are a great way to truly understand some of the common dynamic programming problems. Many of these problem involve exploring exponential combinations and recursion provides a way to explore the combinatorial space systematically. The next steps would be to understand how the bottom up approach explores the combinatorial space for these problems.